The launch brought together over 50 people from all intersections of my life: students and faculty from Berkeley College, John Jay College, and other CUNY schools; NDRI drug researcher folks; sex worker rights activists; Dazzle Dancers and other friends; and of course friends and family from upstate, out of town, and Granny Mansion, where I live in Queens.

It warmed my heart to be able to share my journey with everyone in one space. Many people who couldn't be there were greatly missed - not least my friends from Cambodia. But I hope to do a similar event next time I'm in Phnom Penh.

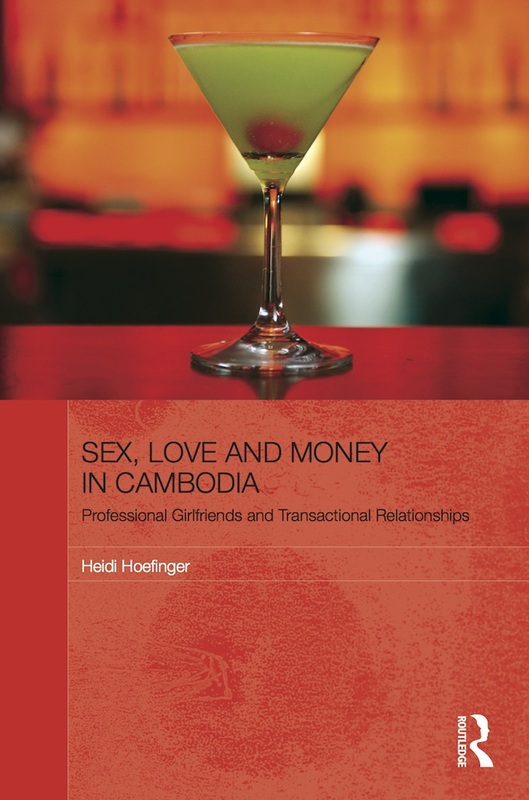

For those of you who couldn't be there, but would still like to purchase a SIGNED COPY of the book, you can do that here at the discounted rate of $50 (which includes shipping within the US!!!).

Simply send $50 to my paypal account using the email address: hoefinger@hotmail.com.

Then shoot me an email with your postal address in the US, and I will send it out straight away.

If you are outside the US, you will just have to pay the overseas shipping fees, plus $50, but we can do it through this same process.

Thanks for all your love and support! Please send me any feedback, comments, reviews of the book here or elsewhere!

With zeal,

Heidi

RSS Feed

RSS Feed