| Here is another installment by VOA Khmer correspondent, Ten Soksreineith, citing my work on intimacy, romance, and transnational relationships in Cambodia! Original article here. This is based on a second interview she did with me, and is the third article that VOA has published on these topics and my work in the past year! The first interview is here, and the second article is here. Thanks Sreinith for drawing attention to these important issues! |

Cambodia

Understanding Intimacy and Economic Pragmatism in Cambodia

Hoefinger travelled to Cambodia as a backpacker in 2003, fell in love with the country and befriended many Cambodian women who worked in Phnom Penh’s bars.

Related Articles

- For Some Women, Sex Work Is a Choice, Not a Matter of Trafficking

- US Professor Examines the Idea of ‘Professional Girlfriends’ in Cambodia

Ten Soksreinith, VOA Khmer, 29 February 2016

PHNOM PENH--Relationships between ordinary Cambodian women and foreign men often are stigmatized as commercial or exploitative. But the truth is in fact multi-layered and complex, as in any relationship where intimacy and material benefit are in play, according to one researcher.

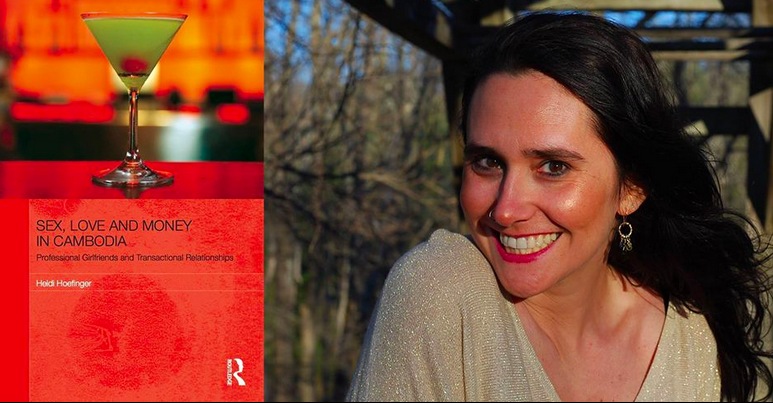

Heidi Hoefinger is a professor at Berkeley College, New York, and the author of “Sex, Love and Money in Cambodia: Professional Girlfriends and Transactional Relationships.” Her unique book examines very closely the lives of Cambodian women who have foreign partners to understand how these women use intimacy to seek socio-economic empowerment.

In an ironic twist in a conservative society like Cambodia, these women are often praised for having “transactional relationship” with foreign men, which bring in money to support their families. But they are also stigmatized for breaking social norms.

In a recent interview with VOA Khmer, Hoefinger explained in depth the interaction between intimacy and economic pragmatism in these relationships.

“In this context of transactional relationships…Cambodian women use intimacy as a tool to initiate and maintain long-term relationships with foreign men, not only to maintain their love, but also to secure material benefits,” she said.

Hoefinger travelled to Cambodia as a backpacker in 2003, fell in love with the country and befriended many Cambodian women who worked in Phnom Penh’s bars.

That turned into an extended period of research, during which she found that some women from rural Cambodia end up working at Western bars and night clubs in Phnom Penh because bar work gives more security, better pay and more freedom in terms of working hours. But the environment in the bars tends to encourage female bar workers to negotiate between their obligation to obey social norms and the decision to seek intimacy and material benefits from foreign partners, which means having premarital sex.

While it is considered taboo in Cambodia, pre-marital sex is widespread. Surveys of schoolchildren have found that 15 percent of boys and 11.2 percent of girls aged between 13 and 15 years old have already had sex, according to the U.N. Population Fund. Rates are predicted to be higher among those not enrolled in school.

For Cambodian women with foreign partners, Hoefinger said that love and material needs are inevitably intertwined. “For the women, emotionality and love are attached to material needs and economic pragmatism,” she said, noting that Cambodian culture has its own ideas about reciprocal exchange linked to marriage.

The colloquial term “milk money” is used to refer to a payment from the groom’s to the bride’s family, in effect paying for the price of the upbringing—or the mother’s milk—of the bride, Hoefinger explained.

“It’s still pretty much culturally expected that when a daughter is married, it brings the material back to the rest of the family,” she said. “So the idea of these Cambodian women desiring a man to help support her and her family should not be attributed to some forms of greed—but sometime it is—rather it is deeply rooted cultural expectation.”

In Cambodia, the line between marriage, transactional sex and prostitution can be ambiguous, she argued. Therefore, all relationships between Cambodian women and foreign men are often labeled as commodified and commercial, inappropriate and inauthentic.

Among Western men there may be a cultural expectation that a woman’s demands for material goods—jewelry and gifts, for example—represent insincere love or intimacy. “This is something that leads to mistrust and uncertainty, which leads to framing the women as ‘greedy whore,’ ‘thief’ and ‘liar,’” said Hoefinger.

Her research also found that, in some cases, “the cultural misunderstanding, the confusion and the mistrust, lead to a lot of different psycho-behavioral consequences,” including emotional and physical violence. This is even more problematic since mental health care provision is so lacking in Cambodia.

“One of my goals is that the research can be used to help facilitate the development of a local and international intervention program that focuses on cultural orientation for couples, relationship counseling, mental health services, depression and gender-based violence,” she said, adding that attention should also be paid to the risks of self-harm, abuse and even suicide among those in cross-cultural relationships.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed