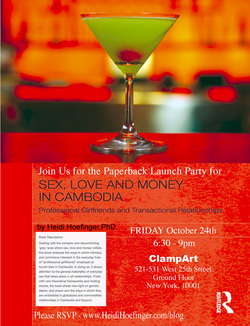

| After months of waiting, the paperback version of Sex, Love and Money in Cambodia has finally been released. I've been holding off on a proper celebration until now so that people can actually afford the book! Please join us in New York on October 24, 2014 at the new venue: ClampArt, 521-531 West 25th Street, at 6:30pm. There will be nibbles, wine and a short reading from the book. I'm looking forward to celebrating and publicly thanking all the wonderful people who have helped make this happen. The event is FREE, but please register for tickets so that we can keep track of numbers: http://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/paperback-book-launch-party-for-sex-love-and-money-in-cambodia-change-of-venue-tickets-13329465791 And if you cannot make it to the event, but would still like to buy the book at the 20% discount, use this code on the Routledge website: FLR40: http://www.routledge.com/books/details/9780415629348/ OR you can find it on amazon! http://www.amazon.com/Heidi-Hoefinger/e/B00ABNB4K6 Thanks! Hope to see you at the launch! --Heidi |

|

0 Comments

Re-evaluating Anti-Trafficking: Cambodian Feminisms and Sex Work Realities

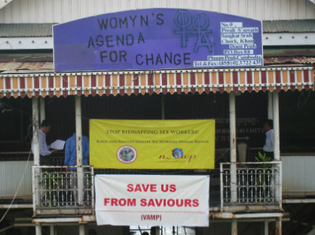

What does feminism look like in Cambodia? It comes in many forms. Women fighting for their rights in response to forced evictions from their land by male-dominated governments and international corporations. Female garment workers striking against their (mostly) male bosses for increased pay and better working conditions. Women politicians trying to have their voices heard within stringently male-dominated politics. Female and transgender sex workers demanding respect and recognition as human beings for the decisions they make to sell sex. The first three examples are fairly uncontroversial territory within feminist debate in that they are generally agreed upon as worthy and acceptable feminist issues—all women should have the right to their land, to better factory work conditions, and to participate in politics. But the fourth example remains a fierce ideological battleground. The dominant feminist discourse around sex work in Cambodia—at least the one most audible due to the hegemony of the international ‘rescue industry’ there—is that of ‘anti-sex work’ abolitionist feminism. Within this model, prostitution is conflated with sex trafficking and is thus always viewed as an act of violence against women; no 'prostituted woman' could ever willingly decide to do this work, and thus she should be rescued from it and taught other vocational skills, like sewing, so that she can participate in forms of more ‘dignified' labour, like factory work; and any 'prostituted woman' who does not identify as a victim in need of saving is simply an objectified pawn of the patriarchy. Hence, the sex industry and sexual slavery (considered one and the same) should essentially be abolished. One of the most visible abolitionists in Cambodia has been Somaly Mam. Cambodian-born Somaly Mam and The Somaly Mam Foundation (SMF) have become globally famous due to Somaly Mam’s efforts in speaking internationally about her own experiences as an orphaned trafficked victim who allegedly spent her life enslaved by various violent men and brothel owners. These stories have been painstakingly detailed in her memoir, The Road to Lost Innocence (2005). As a result of her confessions, and the parading of other female 'victims' of trafficking in front of cameras so that they may describe their abuse in lurid details, Somaly Mam has won prestigious awards and millions of heartfelt dollars. Rich westerners and celebrities, both outraged and moved by the ‘trauma stories’ have generously opened their pockets so that she could continue her rescue work—work which has involved accompanying police on brothel raids in order to rescue women (who do not necessarily want to be rescued) and detaining them in vocational shelters, or sending them to government-sponsored ‘rehabilitation centres’ (which, in Cambodia, are nothing more than prisons). The problem with Somaly Mam’s work is that it has mostly been based on falsehoods and exaggerations. According to investigative journalist Simon Marks, who broke the latest story in Newsweek in May 2014, she was not an orphaned sex slave for most of her young life. Instead, she was raised by her biological parents and attended school until high school (a privilege many girls do not have in Cambodia due to gendered inequities in education). In at least two cases, the young women she paraded in front of the media were not victims of sex trafficking either—but instead persuaded to say so in order to raise funds for SMF and Somaly Mam’s anti-trafficking NGO in Cambodia, AFESIP (Agir Pour Les Femmes en Situation Précaire). After seeing these revelations in print, I am left with two feminist questions: How is this kind of feminised exploitation for gain any different from the male ‘pimps’ and other third parties who profit from the labour of sex workers whom she so vehemently opposes in her abolitionist anti-trafficking work? What have been the consequences of these allegedly false and unethical abolitionist tactics for other sex workers in Cambodia? The answer to the first question is simple: in many ways, it is no different. She has used poor women and fraudulent stories for her own gain and international prestige—which works only to create a credibility issue for real survivors of abuse. She is guilty of exploitation for profit, and the consequences of this, and the anti-trafficking gravy train it has influenced, have been detrimental for many other people in Cambodia who make their livings from trading sex. The anti-trafficking movement that Somaly Mam helped spur (starting with her first public appearance in a French documentary in 1998 with a Cambodian girl who allegedly auditioned to tell fabricated stories of her own sexual slavery), gained momentum when the anti-trafficking agenda became a priority of the Bush Administration in the early 2000s. By 2003, the ‘Global AIDS Act’ and the ‘Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act’ were implemented, which created a series of conditions for organisations receiving US funding for HIV or anti-trafficking programming. One of these conditions was the ‘anti-prostitution pledge’, which required recipients of USAID grants to explicitly oppose sex work and trafficking. Sex worker advocacy groups that did not have these policies in place or that refused to sign the pledge, had important funding pulled. As a result, certain condom programmes ended, and certain drop-in centres for sex workers were closed (Busza 2006). Grassroots community-led groups in Cambodia, such as Women’s Network for Unity (WNU)—the current sex worker union with approximately 6400 members—were directly affected. Most local and international NGOs working with WNU at the time were heavily dependent on US funding, and as a result of the new stipulations, they ended their support for fear that collaborations with WNU would jeopardise their funding (Sandy 2013). Already-marginalised sex workers and their supporters, including feminists of other kinds (namely liberal, Marxist, socialist, or sex radical feminists), were further pushed to the periphery as the abolitionist anti-trafficking bulldozer raged ahead. By 2008, the abolitionist movement had gained so much power in Cambodia that under pressure from the US and UK, the Cambodian government passed the ‘Law on the Suppression of Human Trafficking and Sexual Exploitation’. This anti-trafficking law formally criminalised ‘soliciting in public’ and according to WNU, its implementation was (and continues to be) devastating to sex workers: large police sweeps of parks began taking place, where the possession of condoms was used as evidence of prostitution (despite that in the late 1990s, Cambodia implemented the ‘100% Condom Use Programme’ whereby owners and managers of all entertainment establishments had to enforce condom use as a condition of commercial sex). According to both WNU and a 2010 report by Human Rights Watch titled Off The Streets: Arbitrary Detention and Other Abuses Against Sex Workers in Cambodia, many cis- and transgendered adult women arrested during these sweeps were sent to vocational shelters, or to government run rehabilitation centres where they faced a number of abuses. These included being forced to urinate in the same plastic bags their rice was served in; HIV positive folks were denied their medications, and ‘pretty’ women were sexually assaulted by prison guards and police. The law that was meant to ‘save’ and protect victims of trafficking and prostitutes—who are one and the same according to the discursive and practical conflation of sex work and trafficking—has actually put many more cis- and transgendered women in danger of violence, abuse, stigma, and HIV transmission. Another harmful consequence of Somaly Mam’s efforts, and those of other Western abolitionist feminists, has been the establishment of a culture of permanent victimhood for poor women in Cambodia. Impoverished women who sell sex are all portrayed as duped, naïve, lacking agency—and in need of saving (a convenient subjectivity for those making money off the rescue industry). Whenever I or other feminists contest this construction of powerless sex workers in favour of one that is more focused on agency and self-determination, we are told that we are simply perpetuating patriarchy; that “approving of the 'chosen careers' of such women does little to ground their 'choices' in reality”; and that in “portraying such women as self-reliant, capable, and career-oriented” we are overlooking the “more desperate aspects both of their individual situations and the situation of women in Cambodia in general”. Here, the ‘desperate’ effort of these feminists to continuously position Cambodian sex workers as powerless and incapable becomes clear. Sex workers’ decisions to sell sex (within a stifling system of gendered constraints), and our recognition and respect for those decisions—are very much grounded in reality. And here’s the reality: Cambodia is, indeed, an incredibly patriarchal society. Women live under oppressive patriarchal conditions associated with strict gendered ideals, and on a daily basis, must negotiate the harsh social and moral codes that are meant to control their behaviour (originating from the Chpab Srei –or Women’s Code-- that were written by monks and elite men between the 15th and 19th centuries). These codes require women to stay close to home, to speak quietly, to dress conservatively, to not enjoy sex, and to accept their subordinate position to men, so that they remain ‘virtuous,’ and the household remains peaceful. So, by leaving their homes in search of work, opportunity, and often respite from other, more oppressive conditions or abusive situations, they are breaking many of the social rules, and defying many of the moral codes which keep them subordinate and dependent on men. Thus, it could be argued, they are in fact, resisting and subverting the patriarchy—despite that this is often done in the context of the existing sexual and gendered status quo. Although sex workers’ experiences are heterogeneous and vary greatly across the sex and entertainment sectors, the case could also be made that by utilising men for their own material benefits, some women are undermining the unidirectional exploitation argument by blatantly ‘exploiting back’. And finally, although they are regularly stigmatised as ‘broken’ and ‘stained’, many Cambodian sex workers transgress the boundaries of respectability and challenge gendered double standards by becoming proud patrons and providers for their families, despite that their work is considered unrespectable and immoral. This perspective of self-empowerment is by no means an attempt to ignore or deny the vast structural violence that women in Cambodia must grapple with on a regular basis. Instead, my aim is to point out that feminist perspectives which continually focus on victimhood, exploitation, powerlessness, and patriarchal oppression ignore not only the agency of Khmer women, and the unpredictable fluid ways that power shifts in structurally unequal situations, but also the ways in which young women blatantly subvert 'the patriarchy’ through the decisions they make to sell sex (--decisions which are often made after they have tried other forms of low-wage, ‘oppressive’ feminised labor such as factory work, street trading, or domestic work). By being proactive and attempting to find solutions to, at times, deeply violating social conditions such as domestic violence and poverty through their engagement in sex work, the women challenge perspectives of victimhood, and disrupt the dominant global discourse taking place around their lives. In Cambodia and beyond, sex workers want to be respected for the decisions they make within some very difficult circumstances and constrained environments. They do not all want to be saved by ‘saviours’ who claim to know best. If anti-traffickers really want to put and end to the most exploitative cases of sexual exploitation, they should build trust and alliances with sex workers on the ground who most often have the closest access to these situations--not take away their main livelihoods by abolishing 'sexual slavery'--which is simply an inaccurate framing of the complexities of adult sex work. Perhaps during this critical moment of re-evaluation of anti-trafficking efforts resulting from the fall of the ultimate 'rescue hero', concerned feminists of varying perspectives can come together to turn attention to broader issues such as global racial, economic and class inequalities, neoliberalism, and corporate globalisation, as well as to more localised issues in Cambodia such as gender disparities, rapid industrialisation, land disputes, working conditions, violent governmental suppression and political corruption. Only then can the structural preconditions behind the expansion of the contemporary Cambodian sex sectors—as well as the rights of the workers in those sectors—be addressed. Only then might the needs and desires of women and children involved in ‘real’ cases of sexual abuse and sexual labour against their will, be met. References Busza, Joanna (2006) "Having the rug pulled from under your feet: one project's experience of the US policy reversal on sex work" Health Policy Plan. 21 (4):329-332. Sandy, Larissa (2013) "International agendas and sex worker rights in Cambodia" in Social Activism in Southeast Asia, Michele Ford (ed.), pp. 154-169, London: Routledge.

Sex, Love and Money in Cambodia has been shortlisted for the BBC 4 Thinking Allowed Ethnography of the Year Award. Thinking Allowed is a weekly radio show on BBC 4 hosted by renowned sociologist and criminologist Laurie Taylor (founding member of the National Deviance Conference in the UK). The announcement of the shortlist on the show can be heard here. (If the episode is not yet available to listen to, it will be soon!) My book is the first ethnography discussed by host Laurie Taylor, and selection committee members, Bev Skeggs and Dick Hobbs. The description of the show is: The Ethnography award 'short list': Thinking Allowed, in association with the British Sociological Association, presents a special programme devoted to the academic research which has been short listed for our new annual award for a study that has made a significant contribution to ethnography, the in-depth analysis of the everyday life of a culture or sub culture. Laurie Taylor is joined by three of the judges: Professor Beverley Skeggs, Professor Dick Hobbs and Dr Louise Westmarland. The winner will be announced at the British Sociological Association meetings at the University of Leeds on April 25, 2014. The winner receives £1000. Fingers crossed! JOHN JAY COLLEGE OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE Department of Sociology Colloquium Department of Sociology Conference Room (3232N) Third floor, North Hall April 29, 2014 1:40 - 2:40 pm (community hour) Heidi Hoefinger’s new book analyzes the ways in which intimacy and commerce intersect in the everyday lives of “professional girlfriends” employed at tourist bars in Cambodia. Join us as she explores a new theoretical framework for understand transactional sex and the ways in which gender, desire, and power and embedded in globalized and commodified relationships. Heidi Hoefinger is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the National Development and Research Institutes in New York, an Adjunct in the Department of Anthropology at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, and an Adjunct Lecturer in Gender and Sexuality Studies at the Institute of South East Asian Affairs at Chiang Mai University, Thailand.  I'm excited to announce the latest issue of Studies in Gender and Sexuality which is a special edition focused on Cambodia, featuring papers by me, Melissa Ditmore, Joanna Busza, and Trude Jacobsen,with an introduction by Katie Gentile. The premise of the special issue was first born at symposium that I organized at Goldsmiths College, University of London in May 2010 titled "New Directions in Sex Research - Examples from Cambodia", where Melissa, Joanna and I presented papers on sex in Cambodia. That symposium was chaired by Professor Angela McRobbie. Over dinner we discussed doing a special edition somewhere. Two years later, Melissa and I presented on a similar panel with Trude at the Cambodia Studies conference in 2012, called *Intimate Contexts*. The panel rationale at that conference was as follows: Inter-personal connections, in which sexual activity forms a major component of the nature of the relationship, are by their nature private. The sanction of relationships such as marriage may be performed publicly, but the nuances of daily life often go unrecognized and ill-understood. Only through elite-authored legal texts and didactic codes can such relationships be evaluated in the distant past; rarely does the scholar find a human story upon which to base hypotheses of the lived experience. By contrast, ethnography permits a multiplicity of voices to be heard. The result is a series of conflicting notions of intimate contexts over time, as perceived by scholars whose biases may have prevented them from seeing the true nature of such relationships. This panel seeks to address this imbalance by presenting papers that reorient intimate contexts away from western traditional perspectives and speak to the Cambodian social milieu with its particular historical and cultural trajectories. The papers in this new special edition of Studies in Gender and Sexuality range across debt bondage, commercial sexual transactions, professional girlfriends, and transnational partnerships. My paper is titled "Gendered Motivations, Sociocultural Constraints, and Psychobehavioral Consequences of Transnational Partnerships in Cambodia" (50 free copies are available for download with this link. If that doesn't work, try this link). The paper is about what motivates Cambodian hostess bar workers and western men to engage in relationships, and then what happens when cultural misunderstandings take place and expectations aren't met. Here's the abstract: Global flows of people, information, and capital have created transnational spaces in Cambodia.Within those spaces exists the formation of complex and multilayered interpersonal relationships between people attempting to capitalize on the opportunities created by these flows. The purpose of this article is to describe these transnational relationships, namely, between young women employed in the entertainment sectors in Phnom Penh and their western male partners, while highlighting the racialized and gendered motivations of the global actors, the inevitable sociocultural conflicts/constraints/misunderstandings that arise within the partnerships, and the resulting challenges and psychobehavioral consequences experienced by the mobile and differentiated individuals involved in these postcolonial relational formations. I would love and thoughts or comments!  Rape and sexual violence are very real problems in Cambodia. Not only have there been various (mostly NGO-based) studies related to these issues, but I know from my own longitudinal academic research on sex and intimacy in Cambodia that these are very real issues of concern there. I also know that much more good quality research is needed to both assess the extent of these problems, but also ways to address them in culturally relative and sensitive manners. A new study based on the sexual intentions of young people on Valentine’s Day, fails to do this however. It is, instead, creating intensified fear and moral panic around youth sexuality, which will only lead to more negative consequences—not less. The study, titled, Love and Sexual Relationships: A Longitudinal Study of the Experiences and Plans Of Wealthier Young People Regarding The Upcoming Valentine’s Day In Phnom Penh, 2009-2014 (A Quantitative Study) was privately funded and conducted by independent public health researcher and newspaper columnist, Tong Soprach, MPH. I admire Soprach’s energy and enthusiasm for conducting much needed research around sex and sexuality in Cambodia, and fully support and encourage the capacity building of local research and researchers. Soprach has been a friend and colleague since I began my own research there a decade ago, and still is. However, despite being graciously thanked in the acknowledgements and cited in the text of the final report, I struggle to support research that is ethically, methodologically and analytically dubious. Thus, in the name of creating healthy and open debate with a colleague and friend, I will outline some of the issues I have with the study here. Soprach consulted both myself and a few other academics and professionals prior to conducting the research. The problem, however, is that much of the advice was disregarded, and the study was designed, peer interviewers were trained, the survey was conducted, the data (from 715 particpants) was analyzed, and the report was published online (without any peer-review)—in less than 30 days, from start to finish. Feeling under pressure to conduct a 5-year follow-up to his original Valentine’s study on this same topic in 2009, he ignored concerns over ethical issues, methodological issues, survey design issues, risks related to rushing the study, and risks around how the study may be used to create further panic and fear around young people and sex. And it appears as though that is exactly what it’s doing. Likely due to Soprach’s media connections related to his job as the social affairs columnist for the Phnom Penh Post’s Khmer Edition, the results from the study have been picked up this week by the Phnom Penh Post (headline: “Valentine’s Day Rape Fears”) and the Post Khmer edition, the UK Guardian (“Cambodian Valentine's survey raises concerns over rape and sexual violence”), the Bangkok Post (“More Cambodians Eye Valentine’s Sex”), Cambodian Radio RFI, and Radio Australia—Khmer edition, among others. He has also presented the research at Khmerarak University, and distributed the report to high school principals all over Phnom Penh in the days leading up to Valentine’s Day. My objective is not to point out all of the flaws of the study or the report itself. Instead, I will highlight the most pressing issues. First off, the survey was designed to measure self-reported “intent”—not actual self-reported sexual “behavior”. Thus, while it may be interesting to collect data on what people “might” do on Valentine’s Day, it does not take into account what people actually “did” do—which depends on the context of the situation, as well as other factors, and which may be at complete variance with what the original “intended” behavior may have been. Secondly, the question that was used to measure male intention around gaining sexual “consent” (or the lack thereof, which was correlated with rape in the findings—and the issue of which most of the media coverage concerns) is biased and leading: If your girlfriend does not agree [to have sex on Valentine’s day], what will you do? (Please tick only one) - I will give her more expensive gift with the aim of having sex with her - I will pressure her by taking her far from town to try to have sex with her - I will trick her by staying out til very late, and use a story like I have no key to get into my house, or no one can open the door for me, to try to have sex with her - I will say to her if we don’t have sex we don’t really love each other, to try to get her to agree - I will take her to a Karaoke club and do what I want to try to have sex with her - I will pressure her to watch pornography to try to have sex with her - I will force her to have sex - No, I will ignore sex, and just hang around for fun - Other (Specify) Not only are the options problematic and leading, but the statistic that keeps getting circulated (i.e. in the Guardian: “Survey finds 47.4% of young men in capital Phnom Penh willing to force their partner into having sex this Valentine's Day”) is very misleading and just plain wrong. This is not only because it’s being used by the media to represent all young men in Phnom Penh—when the data from such a small study (376 men) are clearly not generalizable to the whole city, but also because when you look closely at the data, only 61 single males (not in a couple) responded to the above question (another 38 males who are in a couple also responded to this question, but for some reason, they are not included in this statistic of 47.4%) (p. 28-29). 52.6% of those 61 single men actually responded with “I will ignore sex and just hang around for fun.” That number was then subtracted from 100%, and the figure of 47.4% (out of 61 single men) was generated to represent a positive response to the other responses above, which were combined and interpreted to represent “non-consensual” options. To put it simply, 47.2% of only 61 single men answered yes to questions that implied they would potentially engage in coercive behaviors to get women to have sex. While it is troubling that even 29 out of 61 “wealthy” men said they would potentially behave coercively, this is hardly representative of all young men in Phnom Penh, yet it is now a statistic that is being circulating far and wide, further pathologizing and already pathologized country (e.g. whenever I say I do research in Cambodia, people typically associate Cambodia with two things: violence and sex trafficking, because those are the only stories that get media attention). This misleading figure will also likely be used as fuel by the government and schools to continue their abstinence and anti-sex campaigns in the days leading up to Valentine’s day, and to justify the physical policing of guesthouses in order to prevent young people from having sex—which is becoming a regular practice on February 14 in and around Phnom Penh. I believe that Soprach was genuinely well-intentioned with this study (though his research objectives are not well-articulated anywhere in the report). It is clear that he is trying to draw attention to pressing public health issues in Cambodia, such as sexual and reproductive health, HIV, unsafe abortions, and rape. However, many of the conclusions and recommendations made are shaky, at best. For example, in the Discussion section, it is suggested that the increase in young couples planning to have sex on Valentine’s day somehow relates to the females seeking unsafe abortions—a totally presumptuous and unfounded correlation, as no questions are asked about pregnancy and abortion. Earlier on in the report, he uses my own findings on the psycho-behavioral consequences of failed relationships between Cambodian bar workers and their western boyfriends (which can sometimes result from socio-cultural challenges and misunderstandings, and can include self-harming behavior and suicide attempts related to depression and pain of rejection among other things) to suggest that suicide is a real threat among the population in his study when they have sex on Valentine’s Day. He then goes as far as recommending that police provide 24-hour security on the two main bridges in Phnom Penh to thwart suicidal jumpers. The evidence cited to correlate suicide with Valentine’s Day was taken from one Cambodia Weekly article in 2009, whereby a deputy chief of the Intervention Police Unit of the Ministry of the Interior apparently claimed there was an increase in suicides around the day. This may have been true in 2009, but there are no questions whatsoever in Soprach’s survey which measure mental health or suicidal feelings related to sexual activity—thus this recommendation does not relate at all to his actual findings. My intention here is not to completely lambast this study, as Soprach does make some sound recommendations at the end of the report, such as suggesting that public health programmers, parents and teachers should increase awareness around sexual reproductive health, HIV, sexual consent, “sexual rights” (which are vaguely defined in the report), and encourage increased communication around sexual reproductive health among parents and youth. He also encourages young people to use condoms when choosing to be sexually active, and to remember they have a “choice” to have sex or not. These are incredibly important recommendations that make sense. But they are couched (and almost hidden) among the other main messages of the report: sex between young people is dangerous and something to be feared; parents and law enforcement should work harder to police young people’s sex lives; and Valentine’s day—an evil Western holiday—it to blame for rape, suicide, unsafe sex, unsafe abortions, and increased HIV among young people. And the ultimate solution to all this is to remind young people to honor conservative Khmer culture and tradition. However, a return to “conservative” Khmer culture—one that requires young women to be subordinate to men and one that promotes a plethora or gendered double standards and stereotypes—may not be the answer to the above issues. Nor is the policing of guesthouses, bridges and ultimately the sex lives of young people. Nor is conducting—and disseminating on a global scale—hasty and not well-designed research, which is then used to fuel hysteria, fear and moral panic around youth sexuality and sexual behavior. A better solution may have been to pay extra care, time, and attention to developing a genuinely ethical and methodologically sound project that addresses these incredibly sensitive and pressing issues—one that is carefully designed and analyzed, peer-reviewed and collaborative, more objective and less biased, and one that is ultimately youth-centered—perhaps focusing on what the young people themselves view as important tools that could help them to make safer sexual decisions and healthier relationship choices. Creating fear around sex does not stop people from having sex. We know that abstinence campaigns don’t work—look at the US! These anti-sex crusades, and the research that fuels them, are actually dangerous because they disempower young people, whom are left fending for themselves without proper understanding and tools that would help them make better decisions. Exaggerated media campaigns are used to create hysteria, reinforce stereotypes and exacerbate pre-existing inequities. These ultimately serve to justify the agendas of those in positions of authority—not the young people who are in desperate need for good quality sex education and information. It is my hope that future studies on youth sexuality focus on promoting meaningful cultural reflection and change regarding sexual behaviors and gender norms, which may then lead to a shift away from fear-based abstinence programming, and toward more youth-centered, reality based sex education programming. The sexual health and well-being of young people in Cambodia are dependent on it.  The original review on the Erdkunde website can be found by scrolling down towards the bottom of the webpage here. Hoefinger, Heidi: Sex, Love and Money in Cambodia. Professional girlfriends and transactional relationships. 214 pp. and 4 figs. The modern anthropology of Southeast Asia. Routledge, Abingdon and New York 2013, US-$ 145 Unlike the scorcher title of this publication might hypothesize, Heidi Hoefinger presents an in-depth field study on intimate ethnography, connected lives and sexual landscapes in developing Cambodia. Hoefinger, an American development researcher and lecturer of gender studies in Chiang Mai University, Thailand, examines bar-girl subculture in terms of alternative kinship, cross-border relationships and – assumingly most important – the access to assets, money and real estate resulting from sexual services delivered by Cambodian women. The materiality invested to maintain relationships, the global nightscape, the sexual landscape of Cambodia and the entertainment industry are closely connected to spatial, ethnic, political and legal dimensions. Starting with the essential figure of the “professional girlfriend”, Hoefinger is aware of the surely discomforting grey area where transactional relationships, supply and demand collide. In seven chapters that are the result of multi-annual research studies including undercover examinations and interviews with female and male informants, the author shows that the resulting transnational relationships between Cambodian women and their foreign partners (Khmer: barang men) are multi-layered. Gender stereotypes and double standards: Hoefinger highlights the ever-present tensions modern Cambodian women experience between desires to be liberal and sexually modern – along with the growing economy in sectors such as garment, real estate, tourism, art and fashion – while retaining elements of “respectable” Khmer femininity and wholesomeness (p. 131). Surprisingly, the figure of the professional girlfriend who is on the rising trend particularly after the global financial crisis that hit Cambodia’s garment industry and left thousands of female garment workers unemployed and diverted them into the bar and club scene of Phnom Penh. Following Hoefinger’s theory, radical feminist perspectives ignore the voices and agency of postcolonial women who are resisting and subverting the patriarchy. By leaving their homes and properties in the remote rural provinces and moving to cities such as Phnom Penh, Siem Reap or Sihanoukville – the tourist destinations of Angkor Wat and the seaside – young Cambodian women are resisting the demands of contemporary codes that require them to remain subservient (p. 6). On one hand, emotional labour is moving to the marketplace, not only in Cambodia, but also in Vietnam and – with a remarkable history – in Thailand. On the other hand, the phenomenon of taboo-breaking “phallic girls” or “modern global girls” (pp. 17 and 55) mirrors a new emerging sexuality within the Cambodian youth. The existence of transnational partnerships has to be contextualized through the looking-glass of history, gender equality, power, political economy, family and sexuality. Intimate ethnography involves alternative kinship and subculture in Phnom Penh’s three legendary tourist areas: The lakeside (the filled-in Boeung Kak Lake), the strip (a tourist street near the central market, renowned for its debauched nightlife and increasing income of the landowners) and the riverside (several streets parallel to the Tonle Sap River). Within the riverside territory, there are still numerous prime land plots waiting for professional entertainment development to host hostess bars, brothels, karaoke venues and beer gardens (pp. 112–116). Doubtlessly, competition in this sector is increasing. As Phnom Penh continuously expands due to population growth, selected valuable sites will become scarce. Both sexual and real estate landscapes including rent-seeking behaviour of landowners are steadily evolving. Although attitudes around gendered domesticity are changing in Cambodia, according to Hoefinger, female bar managers express frustrations with the position of women in the country and the stigma people have against women who work in bars. Women attach themselves to westerners in the hope of gaining social, sub-cultural and material capital including “a large house and hire domestic help” (p. 166). In addition, a gap between official law and general implementation practice can often be diagnosed. Land law, family law, the Civil Code or the Cambodian Constitution may simply be unknown by the majority of the population, or the legal system can be de facto out of reach for many. The popular transactional relationships have to be contextualized with the inner-Cambodian migration as said above. Field surveys brought evidence about the lack of security in view of joint land titles in particular in the event of separation, divorce, abandonment, multiple marriage relationships (polygamy) or death of the husband. Hoefinger’s work does not only show the materiality of everyday relationships, the expansion of prostitution following foreign troops after 1979 or designing the “emotional geography” in modern Cambodia, far beyond the debate on human trafficking, exploitation and prostitution in Southeast Asia. Instead, Hoefinger offers multiple examples of Cambodian women acting self-confident in the sexual landscapes and who circumvent asymmetries of power. Thus they could turn Phnom Penh into a space of opportunity rather than one of domination (p. 178). The current debate in Cambodia among NGOs underlines this. Women are to have the same rights in marriage as their spouses with respect to ownership, management, enjoyment and the disposal of property. In the final chapter, Hoefinger presents scenarios of positive changes – she calls them success stories – of girls with whom she had consistently communicated with over several years in her research. Some managed to move out of Phnom Penh, back to their provincial villages and families. Indeed, the irony here is that these women found happiness not in the arms of a distant foreign lover, but right in their own backyards and homelands. Some purchased concrete or wooden houses with joint-titled land certificates and open shops. Joint titling of land has generally increased in the Cambodian land distribution program due to pressure from the women’s movement, NGOs and international donors. Joint ownership – in the terminology of the Cambodian Land Law: Undivided ownership – may be interpreted as an important strategy to ensure that the process of formalizing land ownership does not unwittingly produce gender-discriminatory effects. Geographers and ethnographic scientists dealing with “emotional issues” such as transnational migration and access codes to natural resources should have a look inside this unusual, however controversial, Cambodian history from the perspective of gender and sexuality. Fabian Thiel (former Land Management and Planning Advisor for GIZ in Cambodia, 2008-2011) References Marks, S. and Prak, C. T. (2009): Hostesses’ hard choices. Tracing the career paths of Phnom Penh’s hostesses. The Cambodia Daily, 11–12 July, 12–13. Mehrak, M.; Chhay, K. and My, S. (2008): Women’s perspectives: a case study of systematic land registration. Phnom Penh.  On September 4, 2013, I was featured in a radio interview with Jim Stevenson on Voice of America, Daybreak Asia program. The interview was pre-recorded and we originally spoke for almost 45 minutes on the phone. The interview was then edited down to about to 8 minutes, which I'm sure was no easy task for Jim. The final edited version can be heard starting at minute 16.14 of the full podcast that aired on Sept 4, or the specific segment can be downloaded below as an mp3 file.

READ ORIGINAL ARTICLE HERE: Everything You Think You Know About Cambodian Sex Workers Is Wrong HUFFINGTON POST 10/15/2013 3:54 pm by David Henry Sterry I'm always on the lookout for people who have interesting things to say about the strange things that happen in the exchange of sex for money. Heidi Hoefinger, author of the new book, Sex, Love and Money in Cambodia: Professional Girlfriends and Transactional Relationships, is one of those people. Here are some of the fascinating things she has some to say about Cambodian sex workers. David Henry Sterry: Why did you want to write a book about Cambodian bar girls? Heidi Hoefinger: I went to Cambodia 10 years ago as a backpacker and I ended up meeting, and connecting with a few girls really quickly. We identified on lots of levels -- particularly around the way we dressed and danced, and the music we liked -- so we became 'fast friends.' Phnom Penh, the capital city, also had a lawless and edgy magnetism about it and I decided then and there that I wanted to come back to Cambodia and write a book about the women who were at the heart of it all. DHS: What did you expect, and how are your expectations met or shattered? HH: I'm a little embarrassed to admit that when I first went to Cambodia back in 2003, I was filled with all the naïve assumptions and western biases that many people have when they first get there: all the girls are 'trapped' in the bars; they have little decision-making power; they are controlled by bosses and managers; they are all sex workers who are commercially available and negotiable for sex upon any request; and every inter-ethnic couple (Cambodian woman/western man) were commercially-based. Well, I had to confront all those assumptions pretty quickly, because when I got there in 2005 to start formal academic research, I learned right away that something quite different was going on. Most of the girls were working in the bars out of their own free will (to the extent that anyone does in Cambodia or beyond); their sexual decisions weren't controlled by bosses or managers and the women could decide themselves whether or not they wanted to 'go with customers'; and the majority did not actually identify as sex workers, or view their quest for foreign boyfriends as 'work.' They viewed themselves as 'bartenders,' 'bar girls,' or 'bar maids,' and viewed most of the sexual partners that they meet in the bars as 'real' boyfriends. DHS: Did you spend much time in the bars, and what happens on a typical night? HH: During several visits over several years, I spent every night out in the bars with the women. But in addition to that, I spent days with them in their homes, helping look after their kids; or we hung out at the markets buying clothes, or at internet cafes translating emails from western boyfriends, or even out in the countryside meeting their families in their villages. But indeed, the majority of our time was spent going out at night. A typical night out usually begins at the salon, where we would get our hair and nails done. The girls who work in the hostess bars that I was researching -- these are bars where Cambodian women sit and chat with mainly western customers, but also increasing numbers of East and Southeast Asian men -- are able to afford this daily activity due to the increased spending capacity they have which results from the material benefits they gain from foreign boyfriends. After we got dressed, many of them would go to their respective bars and work their shifts from 7pm-2am. After that, we would go to the dance clubs -- with or without their male suitors -- and when those closed, we would end up at the 24-hour bars to play pool. Finally, we'd end the night by having a bowl of soup on the street to catch up on the night's gossip before going home to sleep as the sun came up. DHS: Did you get to know any of these women, and if so, what would she like in terms of background, education, aspirations, dreams, goals? HH: Over a decade, I got to know many of the women as close friends. And though we came from different ethnic, economic, class and educational backgrounds, we shared similar aspirations: to be happy and live in comfortable environments with our material, physical and emotional needs met. Most of the women were born in the Cambodian countryside, and a combination of familial obligation, financial need, and personal aspirations for adventure, freedom or romance drove them to migrate to the cities. Many but not all have elementary educations -- but that's it, so when they get to the city, their options are limited. They can either do domestic work like cleaning, or street trading of fruits or other goods, or garment factory work, or entertainment or sex work. Many tried their hand at everything and ended up preferring to work in the bars because they were the most lucrative, there was more flexibility of movement, they got to meet people from outside of Cambodia, and learn and improve their English skills, and the bars were just generally more 'fun' than the other jobs. Most women are very resourceful and entrepreneurial, and the ultimate goal of many of them was to open their own businesses -- like a clothing store, bar, restaurant or salon, so they could support themselves and their families. Of course meeting a nice person along the way, who treats them and their families with love and respect, was also one of the life goals for many. DHS: Do the bar girls see themselves as sex workers? HH: Actually, the majority of women I spoke to in the hostess bars over the years do not, in fact, identify as sex workers, or their search for foreign boyfriends as work. Yes, they want and even expect, in some cases, to materially benefit from relationships with foreigners, who by default have more economic power over the women by nature of their western positionality, but the women normally don't view these things (like clothes, jewelry, phones, tuition, rent or cash) as payment for sexual services from clients, but rather as gifts or support from boyfriends. Within Cambodian culture, there exists a thing called 'bridewealth' -- which is when the potential groom's family pays the potential bride's family back the money they spent on milk while raising their daughter up -- known colloquially as paying back the 'milk money.' So there is a deeply-rooted cultural expectation of economic benefits attached to marriage. In other words, it's assumed that a man will financially support his female partner and her family -- or at least provide a substantial gift. This is not as rigid as it used to be, and more and more women are equally contributing economically within their relationships, but the point is that just because they get stuff like cash and gifts from their western sexual partners that they meet in the bar does not mean they all identify as sex workers. There are plenty of women, men and transgender people in Cambodia who do identify as sex workers, and there is a growing sex worker rights movement in Cambodia led by a sex worker union consisting of over 6,000 members. But one of the main points of the book is that no matter how someone identifies -- as a sex worker, prostitute, girlfriend, whatever -- they should be treated with respect for the decisions they make. The book is really trying to destigmatize all the actors involved -- the women and their male partners -- whether they are involved in commercial relationships or not. DHS: How are sex workers viewed in Cambodia? HH: Typically sex workers, or entertainment workers in general -- whether they identify as sex workers or not -- are viewed with either contempt by general society, or even as subhuman by others. Otherwise, they are viewed as pitiable victims that need saving (and there are lots of local and international NGOs who make it their business to do so). There are written social and moral codes for women that dictate how they should live (originally known as the Chbap Srei, or Women's Code): quietly, without drawing attention to themselves; obediently and submissively towards their husbands, while not venturing far from home; modestly, in the way they dress, etc. So the women in the bars go against these social codes 100 percent -- they are the epitome of 'bad women' or 'broken women' (srei kouc, in Khmer). But, they can also materially 'make-up' for their tarnished images by providing their families with new houses, cars, and tuition for their siblings. So they experience extreme stigma and praise at the same time. It's a difficult gendered social world for them to negotiate. DHS: Do these bar girls in Cambodia see themselves as victims? Do they long to be saved? HH: Most of the women did not view themselves as victims, and expressed a strong desire to instead by respected for the decisions they make under some really tough circumstances. They often referred to themselves in English as 'strong girls.' That's not to say they didn't know how to capitalize on empathy. That was definitely a strategy that some of the women used to tap into the 'hero syndrome' that many western men experience -- which I define as an overwhelming desire by the men to use their status, resources, and knowledge to 'save' the women and their families from destitution. The problem with 'hero syndrome' is that once men offer their 'help,' they also expect a certain degree of power in decision-making about how those resources are spent. So really, those with this 'hero' mentality to 'help' aren't really helping in the long run if they are just trying to control the families and their finances. DHS: What is the best way for a well-intentioned white Westerner to help then? HH: Cambodia has quite a bit of 'help' already. The country has been heavily funded by international aid agencies since the 1990s and is still a place where SUVs slapped with NGO logos take up far too much space. It's also currently flooded with masses of well-intentioned but highly uninformed 'voluntourists' who actually pay money to volunteer their time at the plethora of dodgy orphanages or schools that line the cities. The country certainly doesn't need more 'help' of this sort. If Westerners have a burning desire to spend their money philanthropically in Cambodia, I would suggest they donate to projects like the Women's Network for Unity (WNU), which is the sex worker union I mentioned above, or to other community-run projects that are led by the women or workers themselves, so that the community members actually have a say in what their needs are and where the resources should be spent. I would not suggest throwing money at the hundreds of anti-trafficking groups that have wasted millions (probably billions) of donor dollars in unrealistically trying to 'abolish slavery' by forcefully 'rescuing' women from the bars, detaining them against their will in 'shelters,' and shoving sewing machines in their hands because that is supposedly a more 'dignified' form of work. Instead, people should 'help' by listening to the women themselves, and to what their needs and desires are, and to respect them for the decisions they make, rather then treating them like infants, victims, or criminals that need rehabilitation or rescue by those who think they know best -- who most often have never even met or spoken to a Cambodian bar worker. DHS: What was your most surprising take away after all was said and done? HH: I guess the most surprising take away from the research is this controversial idea that not all women who work in bars identify as sex workers; that their relationships aren't all commercial and often filled with love and emotion; and that the women aren't all victims who want to be rescued by do-gooder westerners! Instead they are resourceful and using whatever tools are available to them -- in this case sex and intimacy -- to improve their lives and find happiness amidst tons of stereotypes, sexual violence, corruption, and domestic abuse. I also learned that all relationships around the globe mingle economics, intimacy, emotion and pragmatic materiality on some level, and so the relationships that transpire in Cambodian bars are really not so different from more 'conventional' relationships that develop anywhere. Of course there are certain power differentials that are present within these relationships based on economics, nationality and class in many cases, but I guess I'm trying to encourage readers of the book to stop stigmatizing sex and relationships between Cambodian bar workers and western men as something fundamentally different from 'their' sex and relationships, and to recognize the transactionality and materiality of their own relationships. And I think the most important thing I learned is that no matter how women identify, and no matter what circumstances they happen to be in, they are capable of -- and should be valued for -- the decisions they make and that includes their decisions to sell sex, trade sex, and have sex with the people of their choosing. It's my hope that public understanding of the issues outlined in the book might ultimately help to reduce the stigma that most bar workers experience there, which is really at the root cause of all the discrimination and violence they experience. BIO: Heidi is a postdoctoral fellow in drug research at the National Development and Research Institutes in New York, and an adjunct lecturer at Berkeley College in NY, and the Institute of South East Asian Affairs, Chiang Mai University, Thailand. She is actively involved in the global sex workers rights movement, and a member of Sex Worker Open University and X:Talk in London, Sex Worker Outreach Project in New York, and on the program advisory committee for the Red Umbrella Fund, which is an international granting body for sex worker projects around the world. David Henry Sterry is the author of 15 books, a performer, muckraker, educator, and activist. His new book, Chicken: Self-Portrait of a Young Man for Rent, 10 Year Anniversary Edition, has been translated into 10 languages. His anthology, Hos, Hookers, Call Girls and Rent Boys was featured on the front cover of the Sunday New York Times Book Review. The follow-up, Johns, Marks, Tricks and Chickenhawks, just came out. He has appeared on, acted with, written for, worked and/or presented at: Will Smith, Edinburgh Fringe Festival, Stanford University, National Public Radio, Penthouse, Michael Caine, the London Times, Playboy and Zippy the Chimp. His new illustrated novel is Mort Morte. He is also co-founder of The Book Doctors, who have helped dozens and dozens of amateur writers become professionally published authors. They edit books and develop manuscripts, help writers develop a platform, and connect them with agents and publishers. Their book is The Essential Guide to Getting Your Book Published.www.davidhenrysterry |

Heidi Hoefinger, PhDThoughts, experiences, reviews. Archives

October 2016

Categories

All

|

||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed