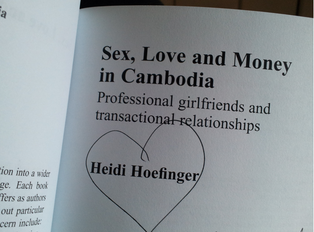

| I'm super excited to have co-authored this chapter titled "Sex Politics and Moral Panics: LGBT Communities, Sex/Entertainment Workers and Sexually Active Youth in Cambodia" with two fierce social justice activists in Cambodia - Pisey Ly and Srorn Srun!!! This is Chapter 27 in the Handbook of Contemporary Cambodia (Routledge, 2016), edited by Katherine Brickell and Simon Springer. It's a major text with over 50 authors covering important topics under five major themes: political and economic tensions, rural developments, urban conflicts, social processes, and cultural currents. As always with Routledge, the cost of the book is astronomical and marketed towards university libraries. If you can put in a purchase request at your school, please do so! It would be much appreciated - Thank you! And if you're interested in just reading a copy of our sexuality chapter, please contact me and I can share the pdf. |

Chapter 27 - Sex Politics and Moral Panics

ABSTRACT

This chapter outlines the two dominant discourses around LGBT communities, sex/entertainment workers, and sexually-active youth in Cambodia that label them as either vulnerable, “at-risk” disease vectors in need of intervention, or as immoral delinquents who are influenced by the west and therefore threats to Cambodian tradition. There has been little focus, however, on the specific rights and social, emotional and political needs of these groups. This chapter is the first academic contribution of its kind to outline the ways in which LGBT communities, sex workers and young people are responding to, and resisting these discourses and addressing their rights and needs through community mobilization and self-advocacy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed