| 2013-09-04_voice_of_america_daybreak_asia_with_jim_stevenson_hoefinger-sex_love_and_money_in_cambodia.mp3 |

| Heidi Hoefinger |

|

||

On September 4, 2013, I was featured in a radio interview with Jim Stevenson on Voice of America, Daybreak Asia program. The interview was pre-recorded and we originally spoke for almost 45 minutes on the phone. The interview was then edited down to about to 8 minutes, which I'm sure was no easy task for Jim. The final edited version can be heard starting at minute 16.14 of the full podcast that aired on Sept 4, or the specific segment can be downloaded below as an mp3 file.

1 Comment

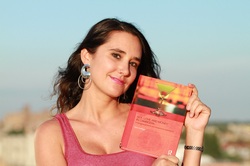

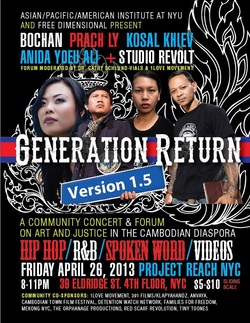

READ ORIGINAL ARTICLE HERE: Everything You Think You Know About Cambodian Sex Workers Is Wrong HUFFINGTON POST 10/15/2013 3:54 pm by David Henry Sterry I'm always on the lookout for people who have interesting things to say about the strange things that happen in the exchange of sex for money. Heidi Hoefinger, author of the new book, Sex, Love and Money in Cambodia: Professional Girlfriends and Transactional Relationships, is one of those people. Here are some of the fascinating things she has some to say about Cambodian sex workers. David Henry Sterry: Why did you want to write a book about Cambodian bar girls? Heidi Hoefinger: I went to Cambodia 10 years ago as a backpacker and I ended up meeting, and connecting with a few girls really quickly. We identified on lots of levels -- particularly around the way we dressed and danced, and the music we liked -- so we became 'fast friends.' Phnom Penh, the capital city, also had a lawless and edgy magnetism about it and I decided then and there that I wanted to come back to Cambodia and write a book about the women who were at the heart of it all. DHS: What did you expect, and how are your expectations met or shattered? HH: I'm a little embarrassed to admit that when I first went to Cambodia back in 2003, I was filled with all the naïve assumptions and western biases that many people have when they first get there: all the girls are 'trapped' in the bars; they have little decision-making power; they are controlled by bosses and managers; they are all sex workers who are commercially available and negotiable for sex upon any request; and every inter-ethnic couple (Cambodian woman/western man) were commercially-based. Well, I had to confront all those assumptions pretty quickly, because when I got there in 2005 to start formal academic research, I learned right away that something quite different was going on. Most of the girls were working in the bars out of their own free will (to the extent that anyone does in Cambodia or beyond); their sexual decisions weren't controlled by bosses or managers and the women could decide themselves whether or not they wanted to 'go with customers'; and the majority did not actually identify as sex workers, or view their quest for foreign boyfriends as 'work.' They viewed themselves as 'bartenders,' 'bar girls,' or 'bar maids,' and viewed most of the sexual partners that they meet in the bars as 'real' boyfriends. DHS: Did you spend much time in the bars, and what happens on a typical night? HH: During several visits over several years, I spent every night out in the bars with the women. But in addition to that, I spent days with them in their homes, helping look after their kids; or we hung out at the markets buying clothes, or at internet cafes translating emails from western boyfriends, or even out in the countryside meeting their families in their villages. But indeed, the majority of our time was spent going out at night. A typical night out usually begins at the salon, where we would get our hair and nails done. The girls who work in the hostess bars that I was researching -- these are bars where Cambodian women sit and chat with mainly western customers, but also increasing numbers of East and Southeast Asian men -- are able to afford this daily activity due to the increased spending capacity they have which results from the material benefits they gain from foreign boyfriends. After we got dressed, many of them would go to their respective bars and work their shifts from 7pm-2am. After that, we would go to the dance clubs -- with or without their male suitors -- and when those closed, we would end up at the 24-hour bars to play pool. Finally, we'd end the night by having a bowl of soup on the street to catch up on the night's gossip before going home to sleep as the sun came up. DHS: Did you get to know any of these women, and if so, what would she like in terms of background, education, aspirations, dreams, goals? HH: Over a decade, I got to know many of the women as close friends. And though we came from different ethnic, economic, class and educational backgrounds, we shared similar aspirations: to be happy and live in comfortable environments with our material, physical and emotional needs met. Most of the women were born in the Cambodian countryside, and a combination of familial obligation, financial need, and personal aspirations for adventure, freedom or romance drove them to migrate to the cities. Many but not all have elementary educations -- but that's it, so when they get to the city, their options are limited. They can either do domestic work like cleaning, or street trading of fruits or other goods, or garment factory work, or entertainment or sex work. Many tried their hand at everything and ended up preferring to work in the bars because they were the most lucrative, there was more flexibility of movement, they got to meet people from outside of Cambodia, and learn and improve their English skills, and the bars were just generally more 'fun' than the other jobs. Most women are very resourceful and entrepreneurial, and the ultimate goal of many of them was to open their own businesses -- like a clothing store, bar, restaurant or salon, so they could support themselves and their families. Of course meeting a nice person along the way, who treats them and their families with love and respect, was also one of the life goals for many. DHS: Do the bar girls see themselves as sex workers? HH: Actually, the majority of women I spoke to in the hostess bars over the years do not, in fact, identify as sex workers, or their search for foreign boyfriends as work. Yes, they want and even expect, in some cases, to materially benefit from relationships with foreigners, who by default have more economic power over the women by nature of their western positionality, but the women normally don't view these things (like clothes, jewelry, phones, tuition, rent or cash) as payment for sexual services from clients, but rather as gifts or support from boyfriends. Within Cambodian culture, there exists a thing called 'bridewealth' -- which is when the potential groom's family pays the potential bride's family back the money they spent on milk while raising their daughter up -- known colloquially as paying back the 'milk money.' So there is a deeply-rooted cultural expectation of economic benefits attached to marriage. In other words, it's assumed that a man will financially support his female partner and her family -- or at least provide a substantial gift. This is not as rigid as it used to be, and more and more women are equally contributing economically within their relationships, but the point is that just because they get stuff like cash and gifts from their western sexual partners that they meet in the bar does not mean they all identify as sex workers. There are plenty of women, men and transgender people in Cambodia who do identify as sex workers, and there is a growing sex worker rights movement in Cambodia led by a sex worker union consisting of over 6,000 members. But one of the main points of the book is that no matter how someone identifies -- as a sex worker, prostitute, girlfriend, whatever -- they should be treated with respect for the decisions they make. The book is really trying to destigmatize all the actors involved -- the women and their male partners -- whether they are involved in commercial relationships or not. DHS: How are sex workers viewed in Cambodia? HH: Typically sex workers, or entertainment workers in general -- whether they identify as sex workers or not -- are viewed with either contempt by general society, or even as subhuman by others. Otherwise, they are viewed as pitiable victims that need saving (and there are lots of local and international NGOs who make it their business to do so). There are written social and moral codes for women that dictate how they should live (originally known as the Chbap Srei, or Women's Code): quietly, without drawing attention to themselves; obediently and submissively towards their husbands, while not venturing far from home; modestly, in the way they dress, etc. So the women in the bars go against these social codes 100 percent -- they are the epitome of 'bad women' or 'broken women' (srei kouc, in Khmer). But, they can also materially 'make-up' for their tarnished images by providing their families with new houses, cars, and tuition for their siblings. So they experience extreme stigma and praise at the same time. It's a difficult gendered social world for them to negotiate. DHS: Do these bar girls in Cambodia see themselves as victims? Do they long to be saved? HH: Most of the women did not view themselves as victims, and expressed a strong desire to instead by respected for the decisions they make under some really tough circumstances. They often referred to themselves in English as 'strong girls.' That's not to say they didn't know how to capitalize on empathy. That was definitely a strategy that some of the women used to tap into the 'hero syndrome' that many western men experience -- which I define as an overwhelming desire by the men to use their status, resources, and knowledge to 'save' the women and their families from destitution. The problem with 'hero syndrome' is that once men offer their 'help,' they also expect a certain degree of power in decision-making about how those resources are spent. So really, those with this 'hero' mentality to 'help' aren't really helping in the long run if they are just trying to control the families and their finances. DHS: What is the best way for a well-intentioned white Westerner to help then? HH: Cambodia has quite a bit of 'help' already. The country has been heavily funded by international aid agencies since the 1990s and is still a place where SUVs slapped with NGO logos take up far too much space. It's also currently flooded with masses of well-intentioned but highly uninformed 'voluntourists' who actually pay money to volunteer their time at the plethora of dodgy orphanages or schools that line the cities. The country certainly doesn't need more 'help' of this sort. If Westerners have a burning desire to spend their money philanthropically in Cambodia, I would suggest they donate to projects like the Women's Network for Unity (WNU), which is the sex worker union I mentioned above, or to other community-run projects that are led by the women or workers themselves, so that the community members actually have a say in what their needs are and where the resources should be spent. I would not suggest throwing money at the hundreds of anti-trafficking groups that have wasted millions (probably billions) of donor dollars in unrealistically trying to 'abolish slavery' by forcefully 'rescuing' women from the bars, detaining them against their will in 'shelters,' and shoving sewing machines in their hands because that is supposedly a more 'dignified' form of work. Instead, people should 'help' by listening to the women themselves, and to what their needs and desires are, and to respect them for the decisions they make, rather then treating them like infants, victims, or criminals that need rehabilitation or rescue by those who think they know best -- who most often have never even met or spoken to a Cambodian bar worker. DHS: What was your most surprising take away after all was said and done? HH: I guess the most surprising take away from the research is this controversial idea that not all women who work in bars identify as sex workers; that their relationships aren't all commercial and often filled with love and emotion; and that the women aren't all victims who want to be rescued by do-gooder westerners! Instead they are resourceful and using whatever tools are available to them -- in this case sex and intimacy -- to improve their lives and find happiness amidst tons of stereotypes, sexual violence, corruption, and domestic abuse. I also learned that all relationships around the globe mingle economics, intimacy, emotion and pragmatic materiality on some level, and so the relationships that transpire in Cambodian bars are really not so different from more 'conventional' relationships that develop anywhere. Of course there are certain power differentials that are present within these relationships based on economics, nationality and class in many cases, but I guess I'm trying to encourage readers of the book to stop stigmatizing sex and relationships between Cambodian bar workers and western men as something fundamentally different from 'their' sex and relationships, and to recognize the transactionality and materiality of their own relationships. And I think the most important thing I learned is that no matter how women identify, and no matter what circumstances they happen to be in, they are capable of -- and should be valued for -- the decisions they make and that includes their decisions to sell sex, trade sex, and have sex with the people of their choosing. It's my hope that public understanding of the issues outlined in the book might ultimately help to reduce the stigma that most bar workers experience there, which is really at the root cause of all the discrimination and violence they experience. BIO: Heidi is a postdoctoral fellow in drug research at the National Development and Research Institutes in New York, and an adjunct lecturer at Berkeley College in NY, and the Institute of South East Asian Affairs, Chiang Mai University, Thailand. She is actively involved in the global sex workers rights movement, and a member of Sex Worker Open University and X:Talk in London, Sex Worker Outreach Project in New York, and on the program advisory committee for the Red Umbrella Fund, which is an international granting body for sex worker projects around the world. David Henry Sterry is the author of 15 books, a performer, muckraker, educator, and activist. His new book, Chicken: Self-Portrait of a Young Man for Rent, 10 Year Anniversary Edition, has been translated into 10 languages. His anthology, Hos, Hookers, Call Girls and Rent Boys was featured on the front cover of the Sunday New York Times Book Review. The follow-up, Johns, Marks, Tricks and Chickenhawks, just came out. He has appeared on, acted with, written for, worked and/or presented at: Will Smith, Edinburgh Fringe Festival, Stanford University, National Public Radio, Penthouse, Michael Caine, the London Times, Playboy and Zippy the Chimp. His new illustrated novel is Mort Morte. He is also co-founder of The Book Doctors, who have helped dozens and dozens of amateur writers become professionally published authors. They edit books and develop manuscripts, help writers develop a platform, and connect them with agents and publishers. Their book is The Essential Guide to Getting Your Book Published.www.davidhenrysterry  Click here for the original article on Globe website with more photos: 'The other Cambodians' http://sea-globe.com/cambodian-returnees-us-immigration-reform/ September 20, 2013 By Dr Heidi Hoefinger Photography by Sam Jam Ripped from their homes in the United States, the Kingdom’s returnees are determined to make the most of a raw deal They started to trickle in at 11am on a sunny morning in Phnom Penh. Curious and excited, old friends and acquaintances began catching up after several years. New arrivals were more timid and unsure of what to expect. This was an historic moment: the first time this group of deported Cambodian-Americans – self-referenced as “returnees”, “homies” and “Khmer-exiled Americans (KEAs)” – were getting together in a self-organised meeting (not one organised by an NGO or church group) to assess their current situations as a collective and decide what they could do with their combined skills and resources. Each person and story is unique, but they share similar trajectories. Chalk C, 37, was born in a Khmer Rouge prison camp. “My mom was in shackles with six or seven other people when she gave birth,” he explained. “The other people that were locked up with her in the hut said [she should] just throw me away because there was no way I could survive with no food to eat. My dad went through some shit to keep me alive. He walked for a day-and-a-half until he saw a makeshift Red Cross clinic.” The majority of returnees were born in Thai refugee camps and, in the early 1980s, were whisked away by American missionaries to various locations in the US, with the largest communities settling in Long Beach, California; Seattle, Washington; Lowell, Massachusetts; and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Once there, many families experienced continued displacement and migration as they tried to resettle and carve out their own communities. “I was born in a Thai refugee camp and don’t remember anything about the move to the US because I was only one-and-a-half years old,” said So, a 30-year-old female returnee. “We arrived by plane in Seattle, then moved to San Antonio, Texas, where we lived until I was about four. We then moved to Fresno, California, before settling in Long Beach for almost 20 years.” Displaced, socially excluded and the brunt of much racial discrimination, many youths resorted to gang involvement for protection and a feeling of inclusion. “I was the only Cambodian in my school,” remembered Tiger, 36, of his experiences in a midwestern Christian school. “Kids would make fun of me, saying: ‘Chinese, Chinese’. I felt awkward. A bunch of older Asian guys needed someone to use. I had to steal and give to the gang to support their habits. I was 13; they were 19. The older dudes made me feel accepted.” Even those who avoided gang involvement would often engage in illegal activities. Eventually they all ended up in the US penal system. In 1996, during the Clinton administration, Congress passed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, which stipulates that any non-citizen living in the US can be deported if convicted of an aggravated felony, with no chance for appeal. As permanent resident ‘aliens’, rather than citizens, many of the Cambodians were charged with additional immigration crimes while serving time for their original offences. “I was so excited, itching to walk out of the door as a free man after serving nine-and-a-half years for my crimes,” said Peye, 37. “But then I was cuffed and sent to immigration prison for a year-and-a-half for a crime I didn’t even know I committed.” Others were released from prison, served their parole and integrated back into the community. Some were out for a few months, or even years, before being “picked up” by Immigration and Customs Enforcement during routine check-ins. One returnee, who wished to remain nameless, had completed his prison sentence 13 years prior to being detained in detention centres and then deported. He left behind three children, a career in laser machine operation and a home, which was subsequently foreclosed. After initially refusing to sign repatriation agreements with the US, the Cambodian government was strong-armed into it in 2002. The deportation flights started the same year, on private chartered jets, with returnees shackled at the ankles and wrists. “Being transported through immigration from one place to the next, it’s trafficking, plain and simple,” said Ko, a 33-year-old returnee. “Coming back [to Cambodia] was brutal, it took almost three days, shackled and waist-chained the whole way.” There are currently about 400 returnees in Cambodia, including 11 females, with some reports estimating that approximately 2,000 Cambodian-Americans are on “the list” in the US, awaiting deportation to a foreign land. Most returnees had never set foot in Cambodia before and, with no predecessors to prepare them for what laid ahead, the early arrivals had it tough. Communication technology and social mobility opportunities were limited. Some returnees clung to their gang mentalities, meaning the group as a whole became associated with violence and were stigmatised. “I couldn’t speak Cambodian. They [Cambodians] could barely understand me. I spoke in street slang,” said Tiger. “I was the quiet type, but we still used to get into lots of fights when we first got here.” Returnees with visible tattoos struggle to integrate into society, while others turn to drugs for survival – as a coping mechanism and a way of making money. As a group, the returnees have gained a bad reputation, and this was part of the reason for the meeting. Attended by a total of 20 returnees throughout the day, the meeting was a chance for them to talk collectively about their issues and figure out ways to assist those already here and also those yet to arrive. Fighting the stigma and dispelling the stereotypes were also on the agenda. “Local people don’t understand us. They see my tattoos, and that’s it; they don’t wanna talk to me,” said Domino. “They’re scared of me. I’m struggling to survive day-to-day.” Among the ideas floated, most were in agreement that a drop-in centre would be a key development. “It could be a space where we could provide our own cultural orientation for new arrivals,” Domino said. “We could help with paperwork and getting people jobs. It could be a place to network and support each other.” A very small organisation, the Returnee Integration Support Centre (Risc), provides some of these services, although it has had to scale back dramatically following major cuts in funding. While Risc still provides limited support to those most in need on a case-by-case basis – particularly those with mental or physical health issues – they are unable to offer the social and cultural network that the returnees identified as important. “Some day, we want to be able to provide housing for those guys who need it the most, like those without family. We also want to give money to startup projects,” said Dicer, one of the earlier arrivals, now aged 45. “Some of us have been here a long time and working in harm reduction. We could provide our own drug counselling, too.” Indeed, a quick brainstorm of the skills and experience they possess as a group throws up abilities from English language and hospitality to marketing and media, from acting and hip-hop to accounting and IT. Trip Locc, a 34-year-old who has been in Cambodia for more than ten years, pointed out that he knew of fellow returnees with practical experience in “masonry, carpentry, construction, car mechanics and hairdressing”. Some of these skills were transferred from the US, while others were developed once the returnees arrived in Cambodia. Current employment for some of the returnee community includes roles in media companies, harm reduction NGOs, mechanic shops, performance groups, advertising agencies and English schools. Understanding the importance of sustainability as a collective, the returnees have floated the idea of setting up their own English school, performance school or training centre, which could help sustain them as a small business or social enterprise. “I am happy with my life and where it is going now,” said So, a female returnee currently employed as a sales executive for an events company. “I have accomplished so much more in Cambodia than I did in the States, but the sad part of my story is that I am separated from my son and my family. They are my biggest supporters, and I wish I could be reunited with all of them. My family just wants to see me happy and doing something with my life. Half a world away, they are proud of me.” This article was written in collaboration with The Other Cambodians, a collective formed by returnees.  Click here for original story on SEA Globe website: “It’s really hard for people to think of Cambodian bar workers as anything other than prostitutes” http://sea-globe.com/heidi-hoefinger-professional-girlfriends-and-transactional-relationships/ September 24, 2013 Interview by: Charlie Lancaster Photo by: Cameron Hickey Sex, Love and Money in Cambodia: Professional Girlfriends and Transactional Relationships is a book collating seven years of research into Cambodia’s sex and entertainment industries. Dr Heidi Hoefinger is its author Why did you choose to spend so many years researching this topic? I fell in love with Cambodia the first time I went there as a backpacker in 2003. The energy of Phnom Penh was frenetic and addictive. I had met a few women in the bars and we became fast friends. We connected through music, dancing and talking about our boyfriends. I decided then that I wanted to spend more time in Cambodia and learn about their lives. I went back in 2005 to start formal academic research on the sex and entertainment sectors, and I’ve been going back every one or two years since. What is the main message readers should take away from your book? There are two really. The first is that the relationships between Cambodian ‘bar girls’ and Western men are complex, not always commercial and often filled with love and emotion. The second is that, despite being surrounded by a sea of gender stereotypes, strict moral and social codes, sexual violence, corruption and domestic abuse, the women are resourceful and use the tools available to them, like bar work, sex and intimacy, to improve their lives. Cambodia can be a tough place to be a woman; and, although their options for supporting themselves are limited, they’ve chosen what’s best for them at a particular moment in time. For the women in the book, that was working in bars and seeking out foreign boyfriends. Many of them had tried other jobs, such as garment factory work, street trading or house cleaning, but bar work was the most lucrative, flexible, educational and sometimes the most fun. Many women learn English and about the outside world through people they meet in the bars. Of course, bar work has its bad points like any job, but these women make the most of their situations and support their families in the best way they can. What were the most interesting findings to come out of your research? For one, the majority of women in the book who work in hostess bars don’t do pre-negotiated ‘sex-for-cash’ and so don’t identify as sex workers – they identify as girlfriends being with boyfriends. Often the boyfriends treat them to gifts such as clothes, jewellery, meals and taxi rides, but it’s not considered payment for sex. The relationships exist in a ‘grey zone’ where sex, love and money all come together. This makes some people uncomfortable because they think these things should never exist in the same space. But one thing I learned is that all relationships – in Cambodia and beyond – combine elements of economics, emotion and intimacy. So, with the book, I’m really trying to get people to reflect on the material and transactional natures of their own relationships and stop stereotyping those between Cambodian women and Western men. Did you come up against any challenges or obstacles? Talking about sex is always controversial. People get emotional and have strong views about what’s right or wrong, good or bad. I’ve found that it’s really hard for people to think about Cambodian bar workers as anything other than prostitutes, and prostitutes as anything other than poor victims, ‘broken women’ or criminals. Saying they are resourceful and even empowered by this work really bothers some people – particularly those who insist on denying the women the agency to make their own decisions. It’s a complicated issue with no easy answers. Also view: “The other Cambodians” – Ripped from their homes in the United States, the Kingdom’s returnees are determined to make the most of a raw deal This morning I received the following email from Paul van der Velde, the Secretary of the International Convention of Asia Scholars (ICAS):

It is my pleasure to inform you - it was already announced during the IBP 2013 Award Ceremony in Macao on 25 June 2013 - that you have won the IBP Reading Committee Ground-breaking Subject Matter Accolade in the Social Sciences for your Ph.D Negotiating Intimacy: Transactional Sex and Relationships Among Cambodian Professional Girlfriends (2010). ICAS is the premier international gathering in the field of Asian Studies. Their International Book Prize (IBP) is a prestigious award granted for both books and dissertations written about Asia in the fields Humanities and Social Sciences. Out of 100 PhD dissertation submissions, mine was chosen for its Ground-breaking Subject Matter in the Social Sciences. My name was read aloud at the 2013 ICAS Award Ceremony in Macao on June 25, 2013. I received my PhD in Social Science and Media Communications from Goldsmiths, University of London, in 2010, under the supervision of Angela McRobbie. It's nice to see it getting some recognition!  Wafts of sweet-smelling pine and skunk drift under my nostrils as he approaches. A broad shouldered, tanned and blond-haired presence in surf shorts and mirrored sunglasses saunters over to the bar and introduces himself. It’s 2003, just after the infamous ‘Blackout’ in NYC and we’re in the dank and dark Bar 169, a Lower Eastside institution on the corner of East Broadway and Essex that was second home to the enigma known in those parts as ‘the Professor’. Looking like an incongruous mix between a California surfer dude and a cop, I would quickly learn that Dr Steve Sifaneck (or simply Dr Steve to many) was a renowned sociologist, drug researcher, and stealthy ethnographer with a literal PhD in cannabis consumption and sales. A decade after that first encounter, Dr Steve graced his local dive bar one last time the night before he left this earth on Sunday, May 19, 2013. A shock to the academic community, and those friends and family closest to him, his premature departure at 46 has left a sudden hole in the lives of many. Students devoted to his ‘fun’, ‘interesting’ and ‘cool’ teaching style, and the way he ‘keeps it real’, were left with confusion and sadness when he didn’t show up to teach his criminology lecture at Berkeley College on Monday. His glowing reviews on ratemyprofessor.com reveal that he influenced a generation of young scholars in the fields of sociology, anthropology, criminology and drug research. And the regulars at Bar 169 surely felt the physical absence of ‘the Professor’ that Monday night. Tucked away in the backroom of the bar, I, myself, mourned the loss of someone, who, a decade earlier, would undoubtedly alter the course of my life and career. Friends first, we spent many an afternoon riding bikes, eating out in Chinatown, or going to see free concerts in the park, such as George Clinton and Patti Smith. But Dr Steve would also go on to be an influential mentor and colleague over the years. In 2005, he was the second reader on my Master’s thesis in Anthropology at Hunter College, CUNY. And in 2006, he introduced me to the Society for the Study of Social Problems (SSSP), an organization and annual conference that would see us present on similar panels in Montreal, NYC, Las Vegas and Denver. He gave useful comments on my PhD dissertation, he graces the acknowledgements of my new book (Sex, Love and Money in Cambodia), and he invited me to guest lecture in his class at Berkeley College. And it is also thanks to Steve that I was first introduced to the National Development and Research Institutes (NDRI) several years back—which is where I currently hold my own postdoctoral fellowship. Known for his PhD research at CUNY Graduate Center on cannabis use and sales in NYC and Rotterdam, Dr Steve also did extensive ethnographic research through NDRI on drug users, drug markets and subcultures, with a focus on global marijuana users and retailers, heroin-using lap dancers in NYC, and Mexican drug gangs and sex workers. At Berkeley, he was currently doing comparative work on global drug policy. During his post at NDRI, he published several papers with Eloise Dunlap, Charles Kaplan, Sam Friedman, Andrew Golub, Ellen Benoit and the late Bruce Johnson, to name a few. And in 2009, Dr Steve and his co-authors (Johnson, Golub, and Dunlap) were winners of the Outstanding Paper Award from Jim Walther for the paper titled An Analysis of Alternatives to New York City’s Current Marijuana Arrest and Detention Policy, (Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 2008). The article was chosen by the editorial team as the journal’s most impressive piece of the year. In addition to his faculty post at Berkeley College, he lectured extensively within the CUNY system, at Hunter College, John Jay, and College of Staten Island. There will be a gap in the program at this year’s 63rd Annual SSSP Conference, taking place in August in New York City, where he was set to present at, and chair a panel titled ‘Global Innovations in Drug Policy’. It was during this same conference in NY in 2007 that Steve led informal tours of notorious historical drug spots in downtown NYC, which was yet another opportunity to flaunt his extensive subcultural drug knowledge. This was the Steve those closest to him knew and loved, as he lived life like an ethnography--an ongoing project of life on the edge. His passing far too soon and sudden, memories of Dr Steve and his important contributions will echo in the halls of sociology and criminology departments for decades to come. Scholar, teacher, mentor, friend…the Professor will be missed.  On the 4th floor of a well-used KTV building in Chinatown, New York City, the Cambodian-American community and their friends gathered on April 26, 2013 to celebrate Cambodian hip hop and arts while drawing attention to the troubling issue of forced deportation that is shaking their community. The evening was momentous. Curated by first generation Muslim Khmer artist, Anida Yeou Ali, and taking place in a space donated by Project Reach (a youth organizing and community empowerment space), the program included live poetry from Anida; live hip hop from Khmer-American rapper, PraCh Ly; and a live set by Neo-Cambodia indie-pop singer, Bochan. The program was interspersed with short films and videos produced by Studio Revolt, an independent artist run media lab and collaborative space based in Phnom Penh, founded by Anida and her partner and filmmaker, Masahiro Sugano. The films included 'Why I Write' and 'Moments in Between the Nights' --spoken word pieces performed by Khmer Exiled American poet, Kosal Khiev, who spent 14 years in the US prison system (which included a year-and-a-half term of solitary confinement) for a gang crime he committed at 16 years old. Kosal had also sent a poignant and personalized video message recorded in Phnom Penh the night before the event, where he described some of his experiences as the informal 'night watchman' of his prison dorm, an experience which inspired him to write, 'Moments in Between the Nights'. The trailer for 'Cambodian Son', Masahiro's documentary about Kosal's life since deportation, and his experiences as London's 2012 Cultural Olympiad, was also screened. Another hit of the night, which brought tears to the eyes of many, was Studio Revolt's piece titled 'My Asian Americana'--a short film which focuses on memories of 'Americana' presented by both exiled and expatriate Asian-Americans living in Phnom Penh. In an show of cultural and national identity, each of the exiles and expatriates were clad in American flags and recited the Pledge of Allegiance to the country which (ironically) deported half of them back to Cambodia. The next film featured the emotional reunion of returnee, Zar, with his wife Tyna in Phnom Penh. Zar was deported back to Cambodia 13 years after having finished his prison sentence. He was ripped away from his wife, children, and job as a laser technician. The film documents Zar and Tyna describing the horrendous day when he never returned home from his ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) check-in. The film is a grim reminder of how devastating these deportations are for those left behind, and how unjust the system is, considering he served his debt to society 13 years earlier for a crime he committed as a teenager. There were also two films dedicated to the work of Tiny Toones, an Phnom Penh-based NGO which provides a safe, positive environment for at‐risk youth to channel their energy and creativity into the arts and education through hip hop and street dance. The first informational film featured the founder and returnee, Tuy 'Kay Kay' Sobil; the second was a new music video collaboration between Tiny Toones and Klap Ya Handz ('an independent hip hop and alternative music family thats changing the face of Khmer music') called 'Anakut', which featured young Khmer youth in a parody of doing grown up jobs. The film segment was followed by a community discussion around social justice and the problems associated with the criminalization and deportation of political refugees. Some audience members bravely took the mic to express their thoughts on the event and the importance of hip hop in the Khmer community. Others, such as Dimple and Sarath stood up to explain a little about PRYSM (Providence Youth Student Movement), and what's being done in Rhode Island and Massachusetts in the fight against racial profiling of Khmer youth. They also spoke about the visibility and growth of the Khmer LGBTQ movement on the East Coast and beyond. In a show of solidarity, both were wearing matching t-shirts that read 'My Color is Not a Crime'. Finally, Mia-Lia from the 1 Love Movement in Philadelphia took the mic to speak about the history of their movement against the deportation of Khmer-Americans. She (and Anida and Dimple) explained that it was ultimately the fault of the US that Cambodians are in America, in the first place, and now it is the fault of the US government that so many Khmer families continue to be ripped apart and experience loss due to deportations. In a nutshell, it was the US government who carpet bombed Cambodia during the Nixon/Kissinger era in the 1970s, which allowed the Khmer Rouge regime to gain power and ultimately slaughter 1.7 millions Khmers. It was then that the US government welcomed thousands of Khmer as political refugees into the US, where they suffered further structural discrimination, disenfranchisement, poverty, and gang violence. It was then ultimately the US government who incarcerated them, and are now forcibly deporting them back to Cambodia--a country many have never stepped foot in since most were born in Thai refugee camps. An audience member stood up and bravely admitted she had never even heard of this issue--a fact that is, sadly, not uncommon, and the reason important events like this one need to continue happening. The night ended with an emotional impromptu rendition of 'Stand By Me' sung by Bohcan, joined by PraCh Ly. They encouraged everyone to participate, and by the end, nearly the entire audience, myself included, had joined them in a show of love and solidarity on the stage. Through the arts, hip hop, spoken word, poetry and discussion, the evening was critically important in drawing attention to the injustices taking place within the Khmer community both in the US and Cambodia. Despite exclusion from the official Seasons of Cambodia Arts Festival programming, Anida and others fought hard to make this event happen. It's another example of the endless fighting spirit of the Khmer community. Thank you for never giving up. |

Heidi Hoefinger, PhDThoughts, experiences, reviews. Archives

October 2016

Categories

All

|

||||||